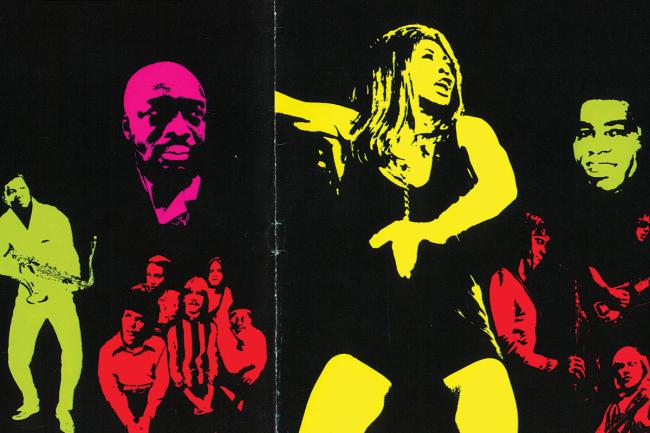

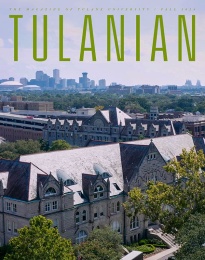

Above: Soul Bowl program cover image courtesy Tulane University Special Collections

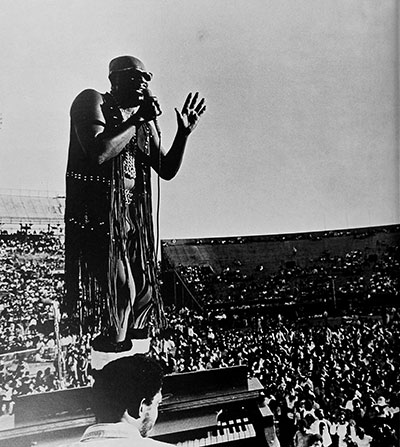

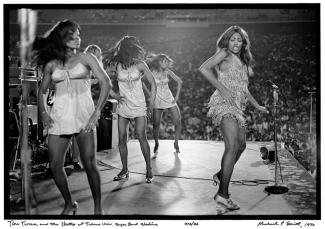

Imagine this. Your favorite artists. An incredible lineup jam-packed in one night. All happening right in front of your eyes and on the 50-yard line of your college campus stadium.

This was the exact case one fall evening in Uptown New Orleans over 50 years ago. On Oct. 24, 1970, Tulane University played host to a show that could easily go down in history as one of the most star-studded collectives ever assembled.

Ladies and gentlemen, this is Soul Bowl ’70.

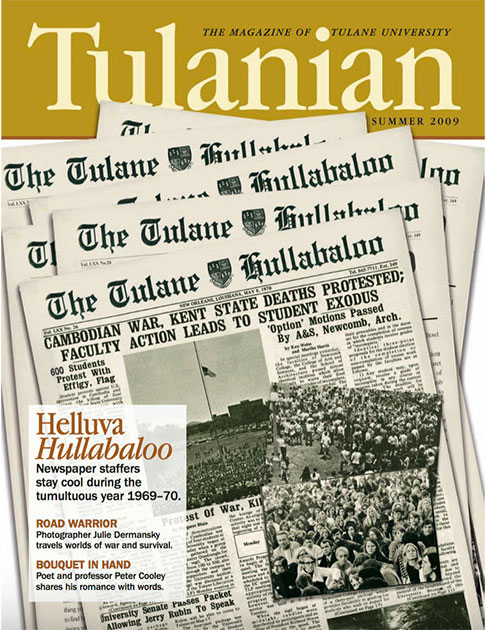

The reality of thinking back more than 50 years ago, in the United States, can bring many to see some stark similarities between then and now. With the 1960s turning into the 1970s, the hope of the new decade was to leave any form of turbulence behind.

Tulane Football even dubbed 1970 as the “Year of the Green” for its expected team success on the gridiron.* However, no sports victory could fully distract communities from significant matters impacting all Americans. From social tensions and rising movements for change to controversies in leadership and international affairs, all institutions met these forces head on, and Tulane was no exception.

As the university was navigating these challenges, an obstacle that also stood tall for Tulane was the expiration of a Rockefeller grant in 1970. Scholarship funds of $500,000, provided by the Rockefeller Foundation, played a vital role in Tulane financially supporting and admitting students of color starting in 1964.

The increased admission of students of color along with their achievement in the classroom helped Tulane to not only become more of an academic powerhouse but also a more culturally enriched environment. Despite the success of this effort, the grant was not intended to be a long-term solution.

Funds from the grant would be fully utilized by the time students graduated in 1973, and Black Tulane students were highly concerned that more solutions for new revenue streams were not being solidified.